Nonviolence

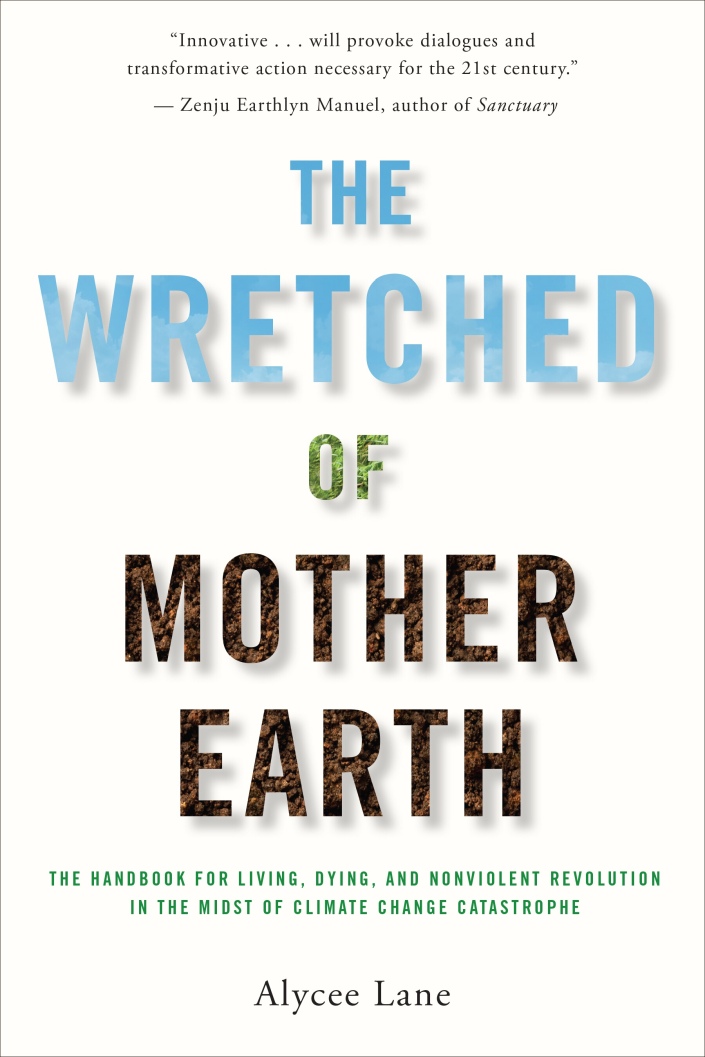

The Wretched of Mother Earth: The Handbook for Living, Dying, and Nonviolent Revolution in the Midst of Climate Change Catastrophe

“Let’s just assume our grandchildren are fucked.”

My new book is out.

Inspired by Sogyal Rinchope’s The Tibetan Book of Living and Dying and Leela Fernandes’ Transforming Feminist Practice, The Wretched of Mother Earth is a mixed-genre Buddhist, feminist, post-colonial, anarchist manifesto about climate change that is also a meditation on dying and death. It is a work in which I argue that if we hope to save ourselves from climate change catastrophe, we must face not only the prospect of human extinction; but also we must radically confront what produced the climate crisis in the first place: the “colonial power matrix” and our deadly attachments to it.

“This [book] is an invitation to experience the transformative power of heartbreak that weaves a healed earth community out of the raw material of grief and fear.” ~Stephanie Van Hook, Metta Center for Nonviolence

Good, bad, or ugly: I invite your reviews of my recent work.

The Wretched of Mother Earth is an ebook that you can order for $4.99 at Amazon (Kindle), Apple (iBooks), Barnes & Noble (NOOK), 24 Symbols, Playster, and Kobo.

“It’s okay, mommy.”

I can’t stop thinking about Dae’Anna – Diamond Reynold‘s four year-old daughter who was in the car when police officer Jeronimo Yanez shot and killed Philando Castile, Reynold’s boyfriend. Specifically, I can’t stop thinking about Dae’Anna’s words to her mom as her mom broke down crying while sitting handcuffed in the back of a police car: “It’s okay mommy. It’s okay. I’m right here with you.”

I have a three-year old who crawls in bed with me whenever I am incapacitated with the pain of a migraine. She lies on my chest, kisses my face and says “It’s okay, momma.” I know that in such moments she is terribly afraid, and that it hurts her deeply to see her momma in such agony. So when I heard Dae’Anna comfort her mother during that incredibly violent, horrific event, I was not surprised, and I knew in my heart of hearts that not only was Dae’Anna unimaginably afraid; she was also in great pain – for her mother, for Philando, for herself. Maybe even for Officer Yanez.

She was also frighteningly vulnerable.

In my heart of hearts I also know that the violence suffered and perpetrated by adults must be answered by turning toward Dae’Anna – toward little black girls and other girls of color everywhere, especially those who are poor – and asking: what is required of us to make the world safe for you? What must we do to ensure that little girls never have to turn to mothers who are forced to flee war, to flee men, who suffer poverty and racism, who suffer through the violence of routine traffic stops and the funerals of kin cut down in the prime of life by state-sanctioned and private acts of violence and say, “It’s okay, mommy. It’s okay. I’m right here with you”?

We turn to them for our answers because it is clear that to resolve the question of their safety and well-being, and (by extension) that of the entire planet, is to commit unhesitatingly to a political, economic, and spiritual revolution that will completely upend the structural and gendered violence by which our society – all of it – is organized and in which all of us are immersed. To turn toward our little girls is to examine, through their eyes, what we have built and to see without blinders the shitty ways we recreate the very circumstances that force them – the most vulnerable in our society – to be their mothers’ comfort and keepers in the midst of violence (slow and fast, visible and invisible) that is also their own trauma and inheritance.

Indeed, if we can ever get to the point where we can say that our girls are safe and thriving — that society is right and just — it will be because we will have courageously and selflessly undertook the labor of radically transforming everything, every damn thing, from the bottom-up. It will be because we will have put to rest the very logic that has created a society that not only renders black people disposable; but that also renders violence “the most important tool of power” as well as “the mediating force” – to use the words of Henry Giroux – “in shaping social relationships.”

Ultimately, if we can ever say that our girls are safe and thriving, it will be because we had come to understand that the meaning and measure of a just society could have only been defined in terms of the needs and care of the least of these. We would have finally understood that this inescapable network of violence (racism, neoliberalism, militarism) — of which war, gun violence (nay, the very ownership of guns) as well as racist, militaristic policing are the articulate expressions — could never have been tweaked or refined or perfected enough to coexist with justice, and that it could have only guaranteed that four year-old black and brown girls would forever be witnesses to, and thus victims of, the horrors it inevitably produces.

So let’s transform the words “It’s okay mommy” into a subversive call to action, into a promise we make to our little girls, and thus to ourselves, that we will transform this world into one where we all – but most especially they – will be absolutely okay.

The House Democrats’ sit-in (or, when nonviolence is violence)

When Georgia Representative and civil rights movement veteran John Lewis likened the extraordinary sit-in staged last week by House Democrats (a sit-in he lead) to the historic 1965 civil rights marches in Selma, Alabama – “We crossed one bridge,” Lewis stated, “but we have other bridges to cross” — he invited us all to see the Democrats’ sit-in as nonviolent direct action in the tradition of the civil rights movement and as an expression of the movement’s highest ideals.

Just as Selma protesters, for example, were champions of nonviolence against the violent and unjust system of racial segregation, the Democrats (Lewis suggested) were champions of nonviolence (i.e., gun control) against a violent system of gun ownership and accessibility, a system that the Republican leadership – through its refusal to allow a House vote on gun control legislation – both upholds and reproduces. And just as Selma protesters persisted in spite of the violent defiance of Selma’s power structure – “it took [Selma protesters] three times,” Lewis reminded us, “to make it from Selma all the way to Montgomery” – so, too, would Democrats persist in the face of House Republicans’ defiance.

The two proposals over which Lewis and his Democratic colleagues staged the sit-in, however, cannot be reconciled with either the Selma movement or with nonviolence. In fact, both proposals – a ban on gun sales to women and men on the FBI’s terrorist watch list, and the expansion of background checks on prospective gun buyers – are so steeped in violence that they effectively render the Democrats’ sit-in, a sit-in for violence.

Consider this: the first proposal rationalizes a system that, as the American Civil Liberties Union points out, is “error prone and unreliable because it uses vague and overbroad criteria and secret evidence to place individuals on blacklists without a meaningful process to correct government error and clear their names.” Indeed, the system is applied in an “arbitrary and discriminatory manner,” such that it functions by and large to target, criminalize, and harass (and thus do violence to) Arab and Muslim communities (ironically enough, Representative Lewis himself was watch-listed, an experience through which he found that the system “provides no effective means of redress for unfair or incorrect designations”).

Furthermore, because the first proposal is justified as a matter of “national security” (as California Senator Feinstein asserted during the course of the sit-in), its function, as Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor argues, is ultimately to “strengthen the country’s security state and to further justify the ‘war on terror.’” That war, according to a joint report issued by Physicians for Social Responsibility, Physicians for Global Survival, and the International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War, has so far cost at least 1.3 million human lives (the cost to the lives of other sentient beings, we must presume, is equally astronomical).

Although seemingly benign in the context of gun control, background checks – the subject of the second proposal – also reinforce a security state framework and, like the first proposal, do nothing to “address the underlying causes of violence in America.” In fact, the proposal – and by extension, the House Democrats’ sit-in – presupposes that the legitimate ownership of guns is the absence of violence. And yet gun ownership is violence, just as the stockpiling of nuclear weapons is violence.

Nonviolent direct action that is not grounded in a transformative commitment to nonviolence, that “neither contests nor seeks alternatives to the dominant imperial mentality of the day” (to borrow the phrasing of Sean Chabot and Majid Sharifi in “The Violence of Nonviolence”), is action that can be easily deployed to champion policies that are, in fact, inherently violent.

Such is how we must view the House Democrats’ sit-in. Not only did the Democrats legitimize legislation that reinforces systemic violence; they also failed to offer anything remotely transformative (such as, for example, legislation that bans guns altogether and commits the United States to international gun control). And they certainly didn’t offer any critique that tied gun violence to “relatively invisible forms of structural, epistemic, and everyday violence” or to our culture of violence.

Imagine if Martin Luther King, Jr. had organized a sit-in on Vietnam in which he called not for the end of the war, “racism, militarism, and materialism” – and not for a “revolution of values” – but merely for the cessation or limited use of Agent Orange.

Given who John Lewis is and the fearlessness with which he confronted the violence of segregationists in Selma and elsewhere, I don’t offer this critique lightly. But as a state actor, he has – along with his colleagues – turned nonviolence on its head. On the floor of the House, the Democrats’ nonviolent sit-in was state violence dressed in nonviolent clothing, and in so being it left unquestioned and undisturbed the structural and spiritual underpinnings that not only shaped the Orlando massacre that triggered the Democrats’ sit-in, but that also continue to drive the everyday visible and invisible violence that continues to roil communities the world over.

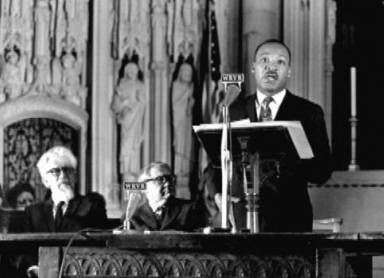

Beyond Identity Politics: MLK’s scathing critique of the Vietnam War in his “most radical speech” troubles today’s identity politics [REPOST]

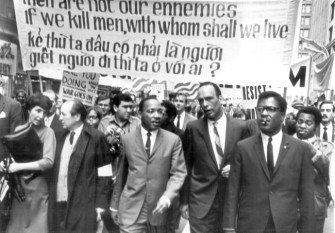

In the compendium of Martin Luther King, Jr.’s speeches, articles, books and sermons, “Beyond Vietnam” stands out to many on the left as the definitive evidence that King had finally become a full-blown radical. King’s speech, they argue, signified his “formal break with…political moderation” because, unlike his previous speeches – which focused primarily on the issue of civil rights – “Beyond Vietnam” took aim (as one critic put it) at “the global struggle of the rich vs. poor.” Even more, it is a speech in which King tied “the American orthodoxy on foreign policy to the structures which perpetrate racial inequality domestically and also to much of the world’s suffering,” as it is also a speech in which he “linked the struggle for social justice with the struggle against militarism.”

For these critics and others, not only did such a critique make “Beyond Vietnam” radical (and King’s “most radical speech” to date); it also made the speech “dangerous” – both to the “political and economic power brokers of America” and ultimately to King himself. Aidan Brown O’Shea, for instance, observed that after delivering “Beyond Vietnam,” King “went from being an admired voice for acceptable racial progress in the form of the end of legal segregation among white moderates,” to being “a truly oppositional figure.” His speech may have even “accelerated,” another critic theorized, “the efforts of those who felt so threatened by” King’s “audacity that they murdered him a year after he delivered it.” In other words, “Beyond Vietnam” was ultimately “the speech that killed” him.

It is to “Beyond Vietnam,” then, that many on the left often turn when they talk about King, and it is the speech they are likely to call upon in order to counter the commemorative “whitewashing” of King’s politics that frequently occurs on August 28 – the anniversary of the 1963 March on Washington – as well as every January, when King’s birthday is celebrated. “Beyond Vietnam,” moreover, is the evidence they provide to rebut conservative efforts to appropriate King’s legacy and to expose the hypocrisy of government officials and others who evoke King to counsel nonviolence and political quietism in the face of injustice. It is even used by some to resist allies’ calls for nonviolence as a way to respond to and organize against unjust governmental action. Ultimately, “Beyond Vietnam” expresses “the real King,” a man who, at the end of his life, was an “anti-capitalist and anti-imperialist political dissident,” the “ultimate anti-establishment man,” a man who had been moving “slowly toward the philosophy of Malcolm X,” and a “democratic socialist.”

Without a doubt “Beyond Vietnam” is a powerful speech, and in my view it is indeed King’s most powerful. Delivered before a gathering of Clergy and Laity Concerned about Vietnam at New York’s Riverside Church on April 4, 1967 – exactly one year before his assassination – the speech is, as John M. Murphy and James Jasinski argued, King’s “most comprehensive indictment of the American war effort,” an indictment through which he construed the war as a war on the poor and as a colonialist project that fed what he called the “giant triplets,” i.e., “racism, materialism, and militarism.” As such, the speech belies efforts to harness King to a conservative, status-quo supporting agenda (which, as is most often the case, tends to be solidly grounded in racism, materialism and militarism).

Moreover, because of this speech, King did face a tremendous and unrelenting backlash from the media, from political elites, from the government, and even from allies in the civil rights community – a backlash that, according to historian Taylor Branch, often reduced King to tears.

The Washington Post, for example, pronounced that by taking a stand against the Vietnam War, “‘King had diminished his usefulness to his cause, his country, his people,’” while Life magazine – engaging in a bit of red-baiting – declared the speech a “‘demagogic slander that sounded like a script for Radio Hanoi.’” The Board of Directors for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) “passed a resolution against what it saw as an attempt” on the part of King “to merge the civil rights and antiwar movements,” and Ralph Bunche, undersecretary of the United Nations, chided King for making “‘a serious tactical error’” by speaking out against the war. Already treating King as an “enemy” of the state, Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) Director J. Edgar Hoover stepped up the Bureau’s surveillance and smear campaign against King, all with the blessing of President Lyndon Johnson who viewed King’s speech as both a personal betrayal as well as an affront to all the work he had done on behalf of civil rights.

Yet, the left’s embrace of “Beyond Vietnam” as a radical text and of King as a full-on radical suffers from its own kind of whitewashing, namely, the subtle cleansing of King of his commitment to nonviolence and love. Almost without fail, when many speak of “Beyond Vietnam” and, more broadly, the “radical King,” they do so either by giving short shrift to King’s continued advocacy of nonviolence and love, or as is most often the case, by subordinating them altogether to King’s “more radical” critique.

In an article where he draws significantly from “Beyond Vietnam” to challenge the “character and political assassination” of King’s work, Eric Mann, for example, tells us that “King was from the outset a Black Militant and revolutionary who advocated non-violent direct action but saw ‘the Negro revolution’ as the overriding objective.” Mann explains that “while” King “strongly argued for non-violence as both a tactical and ethical perspective,” he nevertheless “supported the right of Black people to armed self-defense and allied with advocates of armed self-defense and even armed struggle in the Black movement.”

Notice the way Mann subordinates – through his use of the words “but” and “while” – to “the Negro revolution,” to King’s presumed support for African Americans’ right to “armed self-defense,” and to King’s alliance with those who advocated armed self-defense and armed struggle, King’s commitment to nonviolence. By so doing, Mann gives the impression that King himself subordinated his commitment to nonviolence to all of these other, more pressing issues – or that, at the very least, he put nonviolence and the right of self-defense on equal footing. Mann also implies that King had no quarrel whatsoever with his allies’ calls for self-defense or of armed revolution.

But the truth is a little more complicated. Yes, King did support the right of self-defense, and in his 1959 article “The Social Organization of Nonviolence” – which he wrote in response to NAACP leader Robert F. Williams’ article challenging “turn-the-other-cheekism” as a strategy for confronting white violence – he pointed out that even Gandhi sanctioned self-defense “involving weapons and bloodshed” for “those unable to master pure nonviolence.”

However, King also argued in “Nonviolence: The Only Road to Freedom” (1966) that “it is extremely dangerous to organize a movement around self-defense” because “the line between defensive violence and aggressive or retaliatory violence is a fine line indeed.” Moreover, it is “ridiculous,” King asserted, “for a Negro to raise the question of self-defense in relation to nonviolence” – just as it would be ridiculous “for a soldier on the battlefield to say he is not going to take any risks.” The soldier is on the battlefield, King pointed out, because “he believes that the freedom of his country is worth the risk of his life. The same is true of the nonviolent demonstrator. He sees the misery of his people so clearly that he volunteers to suffer in their behalf and put an end to their plight.”

And in “Where Do We Go From Here,” a speech King delivered before a convening of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference four months after “Beyond Vietnam,” King specifically criticized those who championed armed struggle as an option for African Americans. “When one tries to pin down advocates of violence as to what acts would be effective,” King asserted, “the answers are blatently illogical.” Those who “talk of overthrowing racist state and local governments” as well as “talk of guerrilla warfare…fail to see that no internal revolution has ever succeeded in overthrowing a government by violence unless the government had already lost the allegiance and effective control of its armed forces. Anyone in his right mind knows that this will not happen in the United States.” Declaring that “this is no time for romantic illusions and empty philosophical debates about freedom,” King went on to call for the strategies “offered by the nonviolent movement” and to assert more forcefully that he “still” stood “by nonviolence.”

What’s clear is that for Mann, subordinating King’s advocacy of nonviolence is critical to his project of claiming King as a Black Militant and revolutionary. Yes, King “advocated for non-violent direct action,” Mann seems to suggest, but he kept armed self-defense and armed struggle on the table.

We see the same kind of rhetorical strategy as Mann’s at play in law professor Camille A. Nelson’s “The Radical King: Perspectives of One Born in the Shadow of a King.” Nelson writes, for example, that society “has captured and marketed Dr. King’s message to minimize the revolutionary impetus of much of his work. But the breadth of Dr. King’s work is vast. He taught about Ghandi-esque principles of love and non-violence. But he also chastised the ugly underbelly of American capitalism with its marginalizing consequences for many people of color and poor whites.”

Nelson’s uses of the word “but” locates King’s nonviolence outside of the “revolutionary impetus of much of his work.” Indeed, in one footnote where she discusses how a watered down King is taught in primary and secondary schools, she makes explicit that his nonviolence is anything but radical. She writes, “children are typically taught that King’s nonviolence, rather than his radical message, led him to achieve great success.”

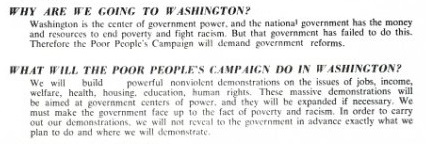

In his article “King’s Transition from the Struggle for Black Political Rights to Economic Rights for All to Death by Hatred, 1955-1968,” Emmanuel Konde didn’t even bother to use – not even once – the word “nonviolence” in describing King’s political “transition.” Given the span of Konde’s analysis, this omission is both remarkable and troubling – and even more so given Konde’s focus on King’s transition to economic rights, for King’s final project – the Poor People’s Campaign – was one he envisioned in terms of “militant nonviolence.” As King explained in “Showdown for Nonviolence” (published twelve days after his assassination), “We need to put pressure on Congress to get things done. We will do this with First Amendment activity. If Congress is unresponsive, we’ll have to escalate in order to keep the issue [of economic inequality] alive and before it. This action may take on disruptive dimensions, but not violent in the sense of destroying life or property: it will be militant nonviolence.”

Konde is not alone in omitting nonviolence from consideration of King’s politics. The word is also conspicuously absent from Geoff Gilbert’s “MLK’s radical vision got distorted,” an article in which Gilbert examines, among other things, how King’s “real legacy on militarism & inequality,” as expressed in “Beyond Vietnam,” has been recaptured by current activists (the protests that Gilbert examines in this article were, ironically enough, nonviolent protests).

One unschooled in King’s work could walk away from these texts and others like it with the distinct impression that nonviolence was no longer important to King and that, prior to his assassination, he may very well have been on the cusp of taking up the call for armed revolutionary struggle.

And yet, not only did King begin to advocate more forcefully for militant nonviolence, which he viewed as both a “positive constructive force” by which the “rage of the ghetto” could be “transmuted” and as an effective means to curb the feverish preparations “for repression” by the “police, national guard and other armed bodies”; but in “Beyond Vietnam” specifically King framed and criticized the war in terms of nonviolence. In fact, in this “most radical” speech he distilled the issues of militarism, racism, and materialism to a question of love.

Identifying the “giant triplets” as symptoms of a “deeper malady within the American spirit,” King argued that the nation needed to heal itself by reclaiming its “revolutionary spirit” and declaring “eternal hostility to poverty, racism, and militarism.” But in order to do so the American people, he asserted, would have to undergo “a genuine revolution of values,” that is, to develop “an overriding loyalty to mankind as a whole” and thus answer the “call for a world-wide fellowship” that “lifts neighborly concern beyond one’s tribe, race, class and nation” – a call that is, “in reality” (King argued), “a call for an all-embracing and unconditional love for all men.”

So why is there all of this whitewashing of King’s commitment to nonviolence and love by some on the left?

It’s fair to say, I think, that conservatives’, government officials’ and other elites’ appropriation of King’s work and image go far to explain why some on the left have erased King’s nonviolence and love. These, after all, are often what conservatives and other elites tend to champion about King’s legacy – though what they offer is empty of anything resembling King’s politics of resistance and ultimately constitutes the kind of “emotional bosh” that King rejected outright. Moreover, the love and nonviolence that conservatives offer are often nothing less than barely disguised expressions of hostility toward African Americans and others.

This hostility was expressed, for example, by talk show host Glen Beck’s call last year for a March on Washington – the 52nd anniversary of the 1963 March on Washington – to protest, under the banner “ALL LIVES MATTER,” “discrimination” against Christians who reject gay marriage (Beck specifically invoked King’s “name to announce” his march and campaign). Not only did Beck attempt to harness the nonviolent 1963 MOW and King’s moral stature to his anti-gay agenda, but he did so by specifically targeting and belittling the organizing that had been taking place – under the hashtag #BlackLivesMatter – against police killings of unarmed African American children, women and men. “ALL LIVES MATTER,” as many have pointed out, signifies a refusal to hear and to redress African Americans’ calls for justice and a radical change in how policing is conducted in this country.

Considering efforts such as Beck’s, reclaiming King from conservative elite appropriation is, I think, an important cultural and political project.

But the conservative game doesn’t explain entirely what many on the left have been doing with King’s work. After all, it’s not as if the latter have, in the face of the conservative onslaught, defended King’s nonviolence and love or exposed the ways that conservatives actually reframe nonviolence in terms that make it compatible with state power and political quietism. If anything, some on the left have, as part of their reclamation project, conceded by omission nonviolence and love to conservative elites.

What I think is driving this whitewashing of King’s commitment – at least in part – is the rather longstanding and yet oft-unspoken assumption among some on the left about what does and does not constitute “radical” politics. As demonstrated above, some assume, in particular, that radical politics cannot possibly include nonviolence; that nonviolence and love are fundamentally incompatible with the kind of critique that King offered; that both nonviolence and love signify, in fact, the absence of radical politics. Indeed, for too many on the left, radicalism is “necessarily bound up with violence” (to borrow from Yale Professor Chris Lebron’s “Time for a New Black Radicalism”).

Viewed in this light, King’s critique of the giant triplets and the war necessarily indicated that he was beginning to abandon nonviolence and love, since one cannot be both radical and nonviolent at the same time. It is therefore entirely in order to excise King’s nonviolence from his critique of the war, materialism, racism, and militarism as well as to align King, even if subtly, with an idea of radicalism he believed was neither revolutionary nor rational.

King, however, challenged outright such a skewed idea of radicalism. Indeed, by marrying in “Beyond Vietnam” his critique of the giant triplets to his philosophy of nonviolence and love, King explicitly defined love itself as the ultimate form of radicalism and as the means by which to reconstruct our society from the bottom-up. “History is cluttered with the wreckage of nations and individuals that pursued” the “self-defeating path of hate,” King lamented in his call for a “genuine revolution of values.” But “love,” he proclaimed (quoting Arnold Toynbee), “‘is the ultimate force that makes for the saving choice of life and good against the damning choice of death and evil. Therefore the first hope in our inventory must be the hope that love is going to have the last word.’”

For King, what made love especially radical was not only that it was the absolute antithesis of the status quo of violence – i.e., militarism, materialism, racism and, of course, the Vietnam War itself; but that it was also, in his view, the means by which we could embrace “sonship and brotherhood” as our “vocation” and thus move “beyond the calling of race or nation or creed” – beyond, that is, the narrow allegiances defined by our political and social identities.

This idea of moving “beyond” such identities (King deployed the word “beyond” several times when he talked about these) and of being “bound” together through and on the basis of love is – more than anything else, I believe – what has compelled some on the left to cleanse King of his commitment to nonviolence and love. King’s construction of both in his “most radical speech” and elsewhere was a clear rejection of what many clearly embrace: a politics grounded in and driven by the reification and reproduction of political and social identities. King implied that not only was such a politics completely inadequate to the task of ending the war in Vietnam; but it was also, he inferred, not a viable basis for radically transforming our society since it embraced the very divisions and ideas of separateness upon which the war, as well as the giant triplets, absolutely depended. For King, this politics of identity put us all on the wrong side of “the world revolution” against the “old systems of exploitation and oppression.” To get on the “right side,” we would have to undergo a “positive revolution of values,” a revolution through which we would come to see ourselves as “bound by allegiances and loyalties” much “broader and deeper” than those prescribed by our social and political identities.

“Beyond Vietnam,” then, is a speech that stands against the kind of identitarian politics that many on the left champion and that ultimately underlie their efforts to “reclaim” King. It was a speech through which he called for the creation of a different form of self – or, rather, called for our embrace of self as love and thus as opposition to, at the level of everyday life, our violent society – which is to say, really, that “Beyond Vietnam” is truly a call to nonviolence, to be the full expression of it and, in the process, to be a force that will reconstruct radically our society into one grounded in and expressive of peace and “brotherhood.”

This is not to argue, as many conservatives would have it, that King advocated or laid claim to some kind of transcendence over race, class, and the like, nor is it to claim that he never embraced these identities. “We must stand up and say, ‘I’m black, but I’m black and beautiful” King declared, for example, in “Where Do We Go From Here.” Reflecting the sexist black power discourse of his day, he declared as well that to “offset…cultural homicide, the Negro must rise up with an affirmation of his own Olympian manhood.”

Yet, King did insist that we are, fundamentally, spirit or love – “that force which all of the great religions have seen as the supreme unifying principle of life,” the “key that unlocks the door which leads to ultimate reality” and which has been grasped by “Hindu-Moslem-Christian-Jewish-Buddhist” belief systems. Thus, even as our lives are undeniably materially and politically shaped by structures that reinforce and perpetuate race, class, nation, and other political/social identities and divisions – necessitating, as King made clear throughout his life, that we organize to dismantle the structural inequalities that these produce and the violence they enact – we are not bound by them. In fact, not only can we move “beyond” them; we must do so, King suggested, for it is our failure to recognize that we are “interrelated,” i.e., connected in spirit and in love (or, as King put it, that we are all “sons of God”), that has set us on a path to “co-annihilation.”

We are still on that path, as our open-ended “war on terror,” our race-to-the-bottom neoliberal economic policies, and the nihilism of our refusal to address climate change all make abundantly clear. In this context, King’s message of love is surely a radical one, a message that asks us to reconstruct completely our society – beginning with ourselves. And it is the King who spoke of love and nonviolence as the path to peaceful coexistence – that radical, unwashed King, whom we must “reclaim” so that we might think more deeply and critically about what is required of us, what kind of revolution of values we must undergo or redefinition of self we must undertake, in order to make a more just and peaceful world. But that reclamation project ultimately requires us to take a hard look at our politics of identity and ask whether or not they are placing us firmly on the wrong side of history.

References

All sources for this article can be found in the original post.

My book is out! Nonviolence Now! Living the 1963 Birmingham Campaign’s Promise of Peace (Lantern Books 2015)

Nonviolence media black-out

Over the course of the recent Baltimore protests concerning Freddie Gray’s death at the hands of police, I received (as did many people I know) several Facebook posts and tweets of pictures that captured what the mass media failed or flat-out refused to cover: the nonviolent protests that took place throughout the city. Those who shared these posts and tweets lamented not only the media black-out of nonviolent protests, but also the media’s absolute focus on violence and violent protests – the looting, the torching of police vehicles, the hurling of bottles and bricks.

As those who shared their posts and tweets noted, the media used the images of violence to narrate the protests not as a story about the brutality that Freddy Gray suffered or about the decades of police repression under which Baltimore’s poor African American citizens have lived or about the grinding poverty that is the lived experience of the community where Freddy Gray grew up (“Baltimore City,” the New York Times recently reported, “is extremely bad for income mobility for children in poor families. It is among the worst counties in the U.S.”). Instead, the media used the images of violence to present Baltimore’s hurt and outraged African Americans as criminals or thugs, as a people so irrational that they would burn down “their own” community – as a people, in fact, who predictably produced a stressed and beleaguered Baltimore police force that has “understandably” resorted to excessive force.

Into this narrative of African American violence the media weaved government officials’ calls for nonviolence – which, as I have argued elsewhere, are nothing less than an appropriation of nonviolence to forward state interests, an appropriation through which officials render nonviolence the language of empire. When the media, then, marginalized the nonviolence on the streets and yet featured officials’ calls for nonviolence, it in essence blacked-out the expression of nonviolence as a radical call for justice and for systemic change. Moreover, it disconnected the violence that it spotlighted from the broader demand and movement for an end to state-sponsored violence (whether in the form of police brutality or economic policies) and, ultimately, from the government’s own unchecked acts of violence.

And yet, we do have those pictures posted on Facebook and Twitter. Clearly, our camera phones will be just as crucial to reframing nonviolence and disrupting both the government’s and media’s narrative of it as they are to capturing police agression and brutality.